General view over valley in mountains of south Norway from beside Lendbreen glacier is seen in this undated handout picture

(photo credit: REUTERS)

Due to global warming, high-elevation ice patches and glaciers have recently yielded a myriad of historical finds for archaeologists to discover.

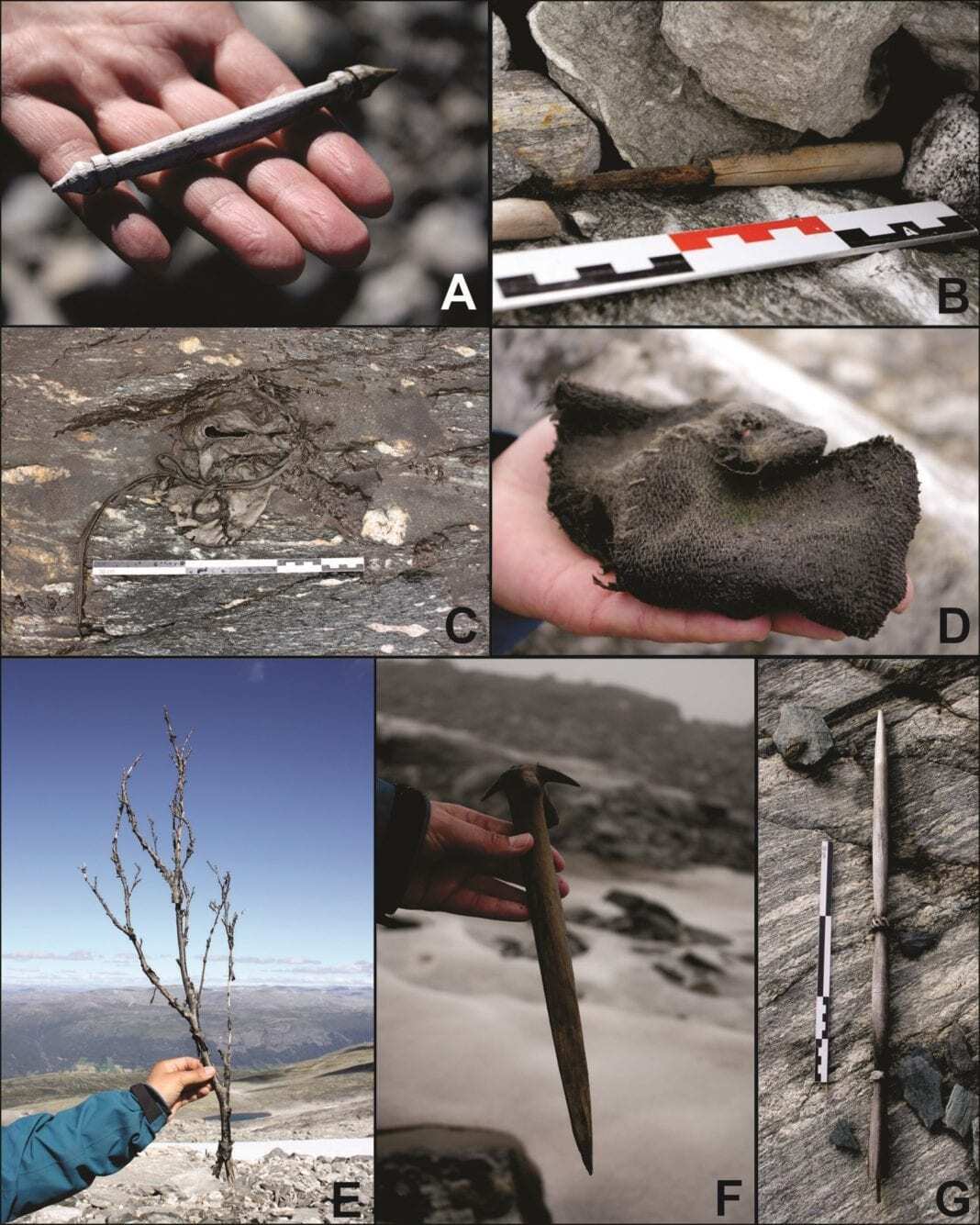

Archaeologists have uncovered a heavily traversed glacial mountain pass in Lendbreen, Norway, utilized by travelers throughout the Viking Age, and littered with hundreds of artifacts presumed to have been used by the Vikings during that time period, according to a new study published by the Cambridge University Press on Wednesday.

Due to the warming global climate, high-elevation ice patches and glaciers have recently yielded a myriad of historical finds for archaeologists to happen upon as they finally gain access to these areas after the layers of ice once covering them have gradually melted away over time – and much faster recently.

Read the rest of this article...